Kinchela Boys Home History

Kinchela Boys Home was built on the stolen land of the Dunghutti. We would like to acknowledge the Dunghutti and other First Nations peoples of this country whose boys were kidnapped under the policies that created the Stolen Generations.

The Boys 'Home'

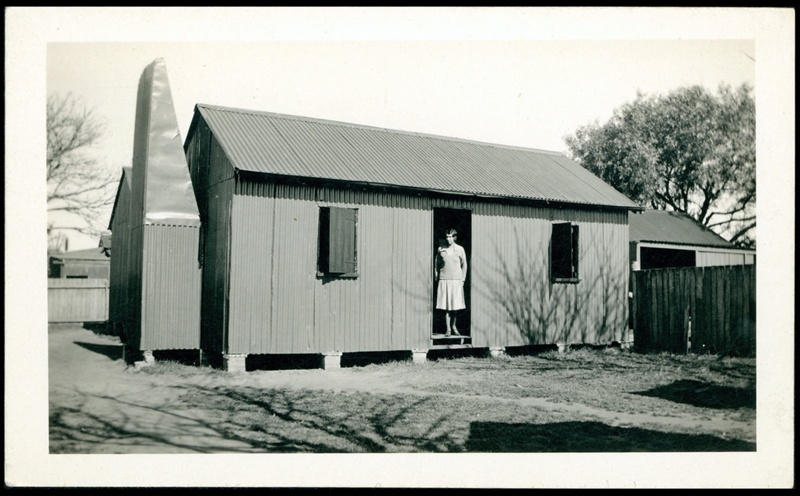

Kinchela Aboriginal Boys Training Home (KBH) was a ‘home’ run by the NSW Government for over 50 years (1924 – 1970) to house Aboriginal boys forcibly removed from their families and deliberately re-programmed in order to assimilate them into white Australian society. Built on the stolen land of the Dunghutti, KBH holds memories, painful and otherwise, for Survivors, and it is a place of deep importance for them, their families, and communities.

The place itself, historical records and the memories and stories of survivors provide tangible evidence of destructive past Government policies and practices for the education and understanding of all Australians

History of Kinchela Boys Home

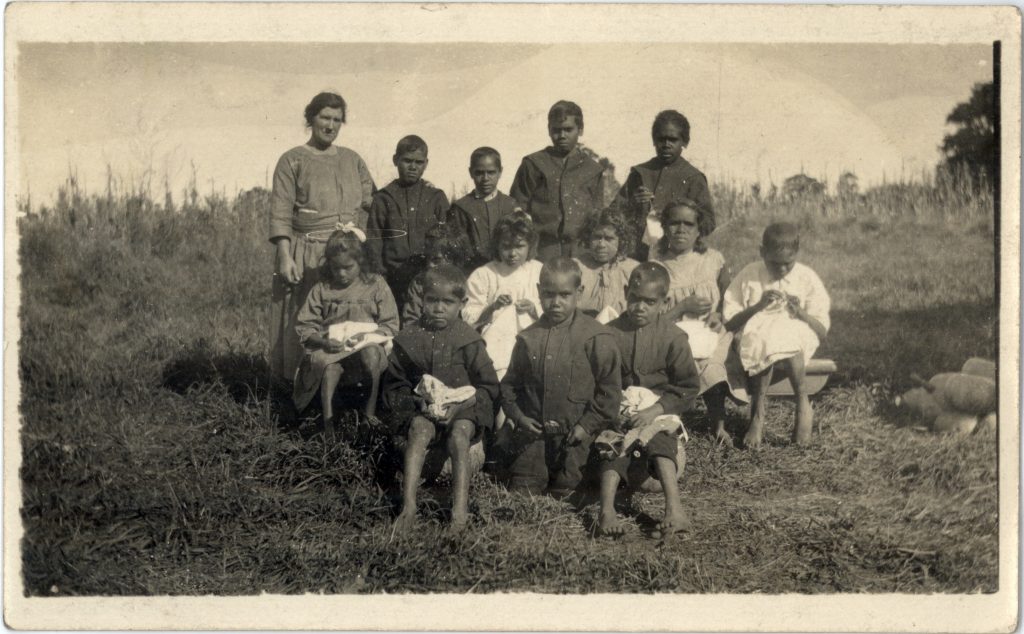

From 1924 to 1970, under the authority of the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board and its successor, the Aborigines Welfare Board, between 400 and 600 young boys (and a small number of girls in its first year of operation) were incarcerated at the Kinchela Aboriginal Boys Training Home (Kinchela Boys Home) on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales, on the stolen land of the Dunghutti.

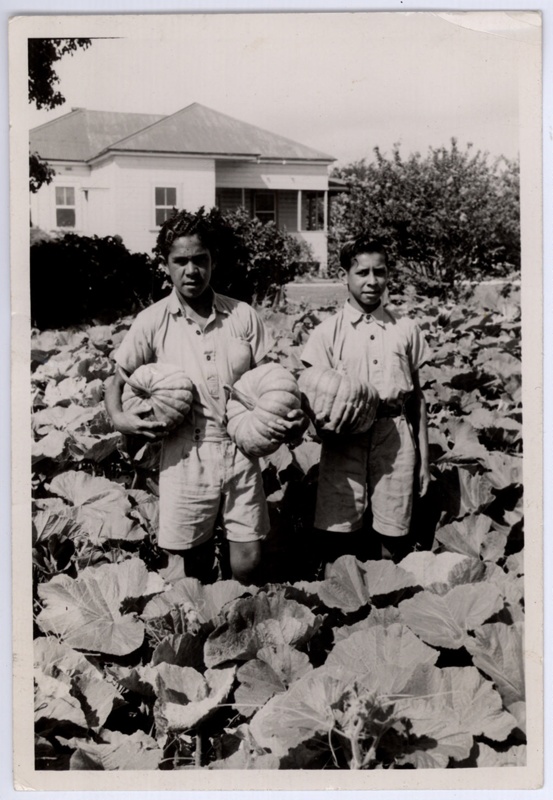

These children are among thousands across Australia who were systematically kidnapped from their families and communities under accepted government and church policies and practices that created the Stolen Generations. The intent was to re-program them to become ‘white’, an act tantamount to cultural genocide.

Kinchela Boys Home is one of the most notorious institutions associated with the Stolen Generations. Conditions within the institution were harsh and hostile. This was a place where physical hardship, punishment, cruelty, alienation and abuse (cultural, physical, psychological and sexual) are documented as having been part of the day-to-day life endured by boys who were kept and made to work there.

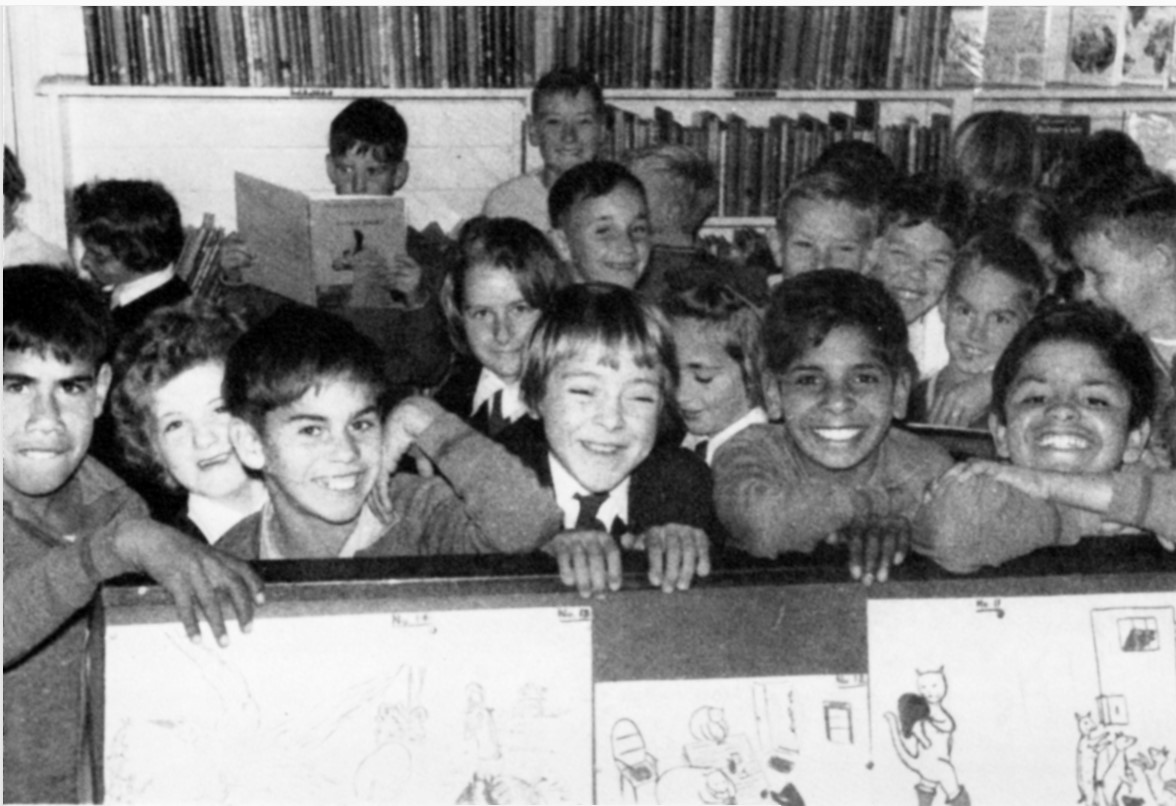

We Were Just Little Boys

Kinchela Boys Home Aboriginal Corporation released We were just little boys for NAIDOC Week 2022. Narrated by KBH survivors and illustrated by Uncle Richard Campbell, #28 it is not only an important contribution to truth telling, but is an evocative glimpse into the lived-experiences of the KBH atrocity.

Legacy of the 'Home'

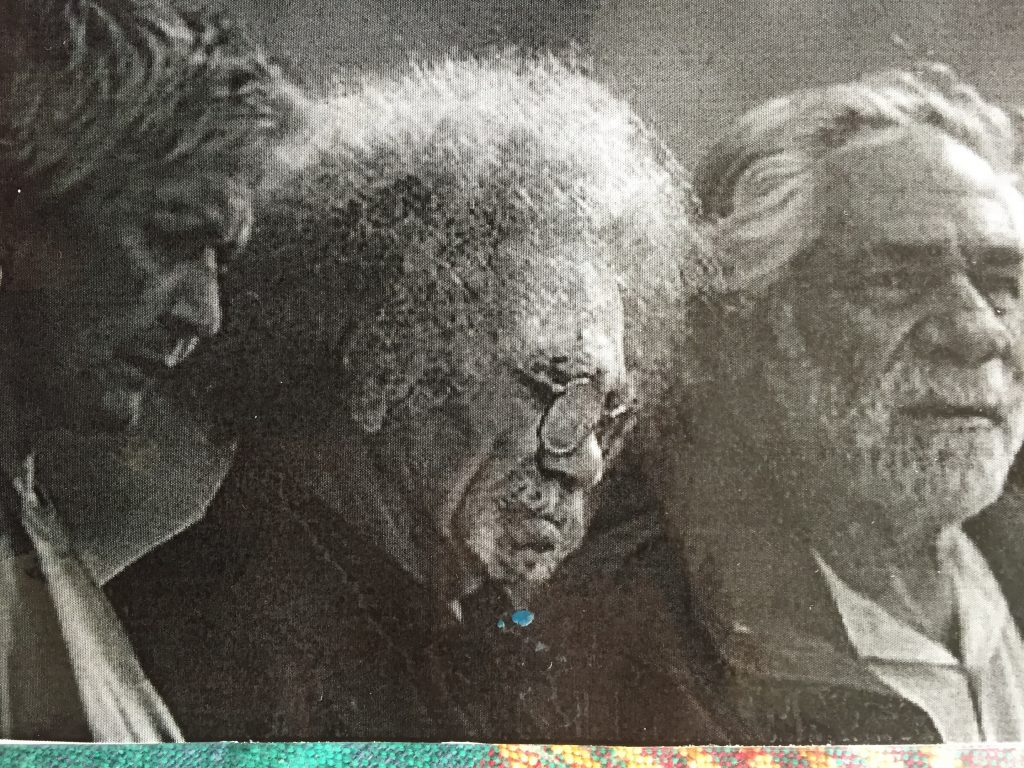

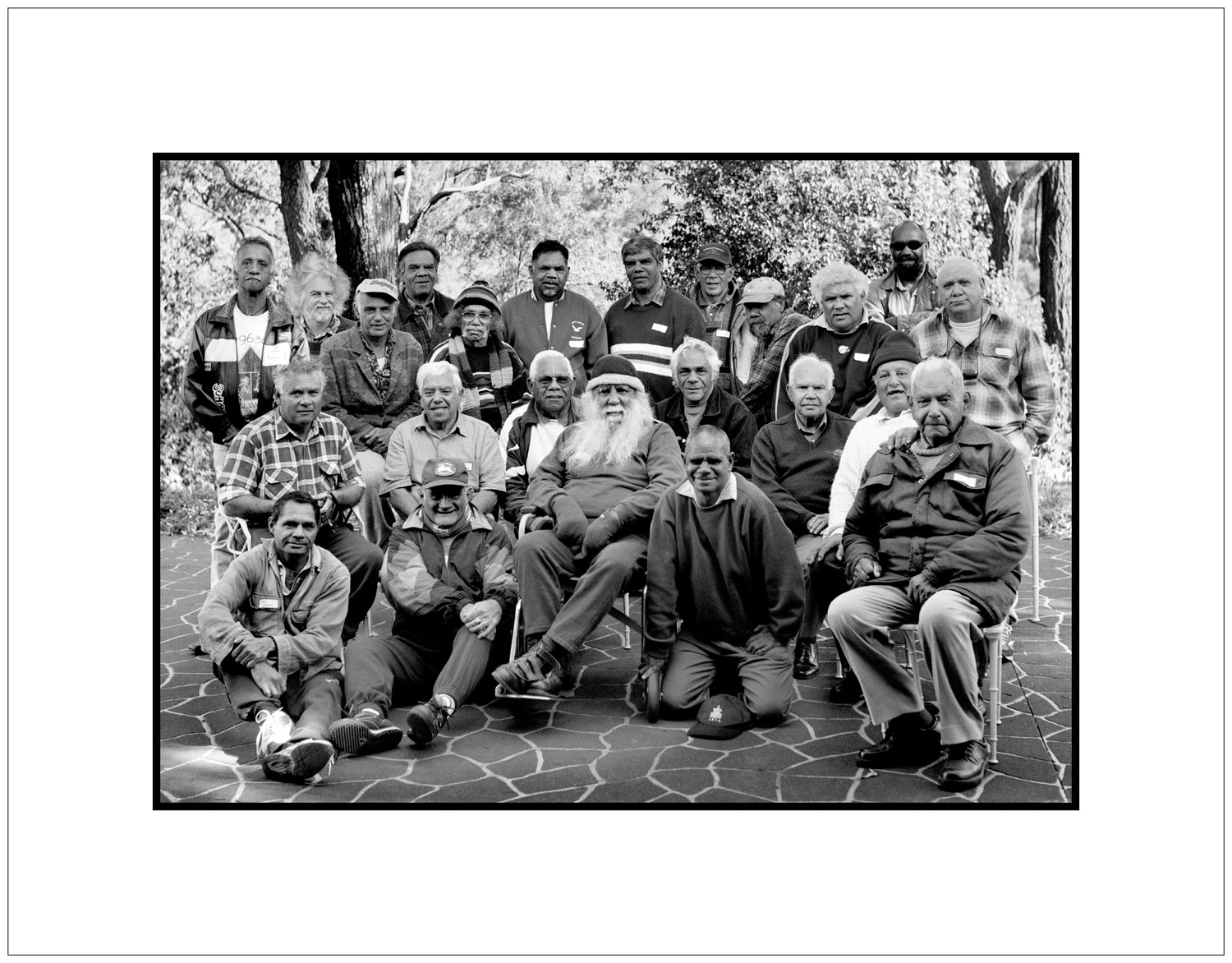

Upon ‘leaving’ Kinchela Boys Home, the boys’ troubles did not end there. Institutionalisation and the legacies of their treatment have resulted in ongoing pain and trauma for survivors, their families and communities. The devastating effects continue to be felt by the descendants and families of the men, who struggle with intergenerational trauma.

Today, the former Kinchela Boys Home site is a place of deep significance to survivors, their families, the communities they were taken from, the communities in the Macleay Valley and the broader community. As part of a long and complex healing process, the site and its deeply personal values must be shared with wider Australia.

Remaining buildings, landscape features and important spaces offer insight into the operation and conditions of the institution. This physical evidence of the reality and legacy of the Kinchela Boys Home, now provide the basis for truth telling. Envisaged to become a museum for the rich collection of oral and historical material already gathered, the site is entering its next phase. After having been silenced and made invisible, the story of the Kinchela Boys Home is once again set to become visible there at the site.

Read more about the heritage listing of the former Kinchela Boys Home Site, the Conservation Management Plan, and the plans for a museum at the KBH site.

Kidnapping Locations

The map below traces the locations of the kidnappings, between 1924 and 1969. Each dot represents a boy and where he was taken from.

Note: Information on this map is based on KBH Admission Records which were incomplete. From these records the location of at least 21 children is not accounted for. Click here to see the full list of KBH Survivors.